The wood steps groan under foot as we descend into the basement. It smells of leather and saddle soap and aging paperwork down here. The scent is genuinely rugged in a way no designer cologne has managed to imitate in decades of trying.

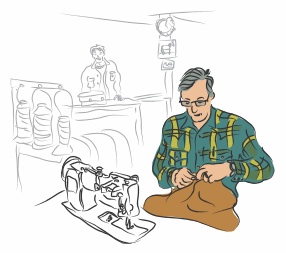

Rawhide straps dangle from the ceiling. Splattered containers of leather dyes and conditioning oils teeter on shelves lining the walls. Brass buckles tacked to the front of wood drawers create a kind of crude hardware filing system. The work bench is littered with scraps of hide and hand tools that look more at home in a museum than a functioning business.

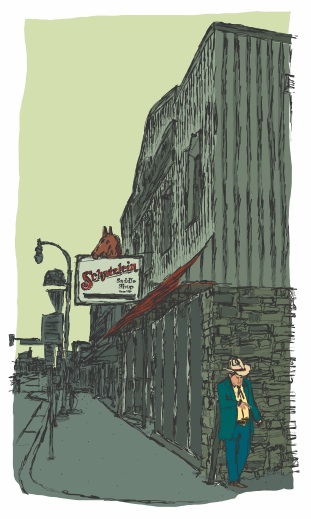

Yet here it is. A working saddle shop in the heart of Southwest Minneapolis, operating in essentially the same spot Emil Schatzlein opened the doors over a century ago.

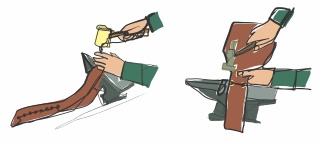

Emil’s grandson Gary Schatzlein, who runs the place now, is bent over an anvil that looks like it might have been ordered by Wile E. Coyote out of an ACME catalog. He hammers a metal rivet into a leather fender (the part of a saddle that sits between the stirrup and the horse’s side the protect the animal from the rider’s boot).

“Back in the early 1900’s, cars weren’t out yet.”

His voice is soft with a hint of aw-shucks charm as he talks about Schatzlein’s early years. He paints a picture of a busy little shop in the country, surrounded by farm fields. Farmers unhitching teams of horses from their plows, pulling them up to the back door to have their harnesses mended right on them. City folk riding in on their horse and buggy for quick repairs after a day meandering the bridle paths around the Chain of Lakes.

“We were kind of like a mechanic, I suppose.”

Back at the top of the stairs an abridged history of Schatzlein’s plays out on a wall of yellowing news clippings and dog-eared photos.

There’s a picture of the original shop at 609 West Lake Street. It’s Dulano’s Pizza now, but a few years ago you could look through a missing ceiling tile and still see the telltale oval marks above the door where horse collars hung—the leather oil slowly weeping into the wall over decades.

Another photo from the late 1930’s shows the store in a new location at 421 West Lake Street, just next to where the shop stands today. A sign hanging in the window reads “Dog Muzzles”. The city had passed a law requiring dogs to wear them in public. Opportunity knocked, and Schatzlein’s answered. People lined up with their pets to have their muzzles custom fit right on the spot (or the Fido or the Rover).

But in the same photo is another sign. A sign of things to come. Parked in front of the store—where only moments earlier someone might’ve untied a horse and ridden away—is a shiny, chrome-and-steel, late-model horseless carriage. Detroit’s finest.

Cut to 1958. Emil’s son, Jerry Schatzlein, had just taken over the store. He’d seen the last horse disappear from Lake Street only a few years earlier. It was tough times for saddle repair. His customers had traded in their horses for horsepower.

Then—legend has it—a salesman walked into the store with the future folded under his arm. He looked Jerry in the eye and told him times were changing. The store just couldn’t make it in saddles alone anymore. “You gotta have these,” he said. And he tossed a pair of Levis 501’s on the counter.

Fifty-three years later, Gary Schatzlein nods toward a rack of 501 shrink-to-fit jeans.

“We still sell the shrinkers.”

And they were only the beginning. He leads us through the store, weaving through a Dewey Decimal system of denim. Racks upon racks of 501’s, 505’s, 510’s, 511’s, 514’s, 517’s, 527’s and so on. Lee’s and Wranglers, too. He tells us he sells a lot of skinny jeans to kids from the punk rock record shop next door.

“They come in with their mohawks, all multicolored, sticking straight up in the air.”

He smiles and shrugs like he’s as puzzled as anyone by this turn of events. Jeans, it seems, are the great unifier.

Since the day that salesman walked into the store, apparel has been a cornerstone of Schatzlein’s business, helping a little country saddle shop thrive even as the city spun a web of smooth, tire-friendly pavement around it.

In addition to jeans, there’s enough western wear here to outfit the cast of a John Ford epic (defenseless townspeople included). Oiled dusters, western-style Swedish knit sport coats and matching slacks, embroidered shirts with mother-of-pearl snaps, gleaming belt buckles and bolos. On one side of the store is a big wall of Stetsons. On the other, an even bigger wall of cowboy boots.

But it’s not all wild west. There’s riding gear in the English tradition, too. Equestrian helmets, laced boots with gracefully arced calves, and camel-brown riding pants. A mom strolls through the store with her little girl in tow looking to outfit her for the summer horse camp season.

Saddles may have been pushed to the back of the store, but a hundred years of heritage can’t be rubbed out that easy. They still sell plenty. Both Western and English. Riding tack, too—bridles and bits and harnesses and stirrups. People still bring their horses to the back door (in trailers, these days) to have saddles custom fit on the animal. Some things never change.

Traffic passing on Lake Street is decidedly equine free these days. Gone are farm fields and bridle paths. Now, instead of a little main street cafe, there’s an Ecuadorian Restaurant up the street. This is what progress looks like. It happens in tiny increments over the course of decades. Easy to miss unless you’re really paying attention.

But there are plenty of Schatzlein family members ready to take the reigns no matter what the world throws at them. So it seems inevitable that there will always be a Schatzlein’s Saddle Shop on West Lake Street. Even if horses somehow disappear from the face of the Earth. Or punkers stop buying skinny jeans.